Click here to view original web page at breachmedia.ca

Trust in Canadian media has reached a new low.

A new study from Reuters Institute found just 42 per cent of Canadians surveyed said they trust “most news, most of the time.” It’s the latest in a long decline in confidence, which is even lower with people under the age of 35—among whom less than a third said they trust the media.

“Canada still remains among the countries with relatively higher trust levels, but this position is not as reassuring as in previous years,” the Digital News Report states.

The crisis in Canadian media isn’t just a crisis of confidence. It’s intimately tied to decades of consolidation and the concentration of power.

If there’s any one factor that has led to the decline in trust in media institutions, it’s the profit-making nature of the enterprise—from devastating disruptions and cuts caused by market shifts, to skewing effects of advertiser-dependent business models, to disproportionate editorial influence by the ultra-wealthy.

The need to develop a common long-term vision of a vibrant, diverse, publicly funded and dominantly nonprofit media ecosystem has never been more pressing.

Postmedia, post-journalism

Media in Canada has undergone several waves of mergers and acquisitions, each creating the possibility of further concentrations of control. The biggest consolidation happened around 2000, with mergers worth more than $80 billion.

Homegrown media titans of the late 90s—Canwest Global’s Asper family and Hollinger’s Conrad Black—eventually ran into financial trouble. Both empires were considered heavily centralizing forces at the time, and eventually became part of Postmedia, which was founded in 2010 and is owned by New Jersey hedge fund Chatham Capital.

Conrad Black started the National Post as a right wing competitor to the Liberal-leaning Globe and Mail, investing millions and sustaining annual deficits as part of a political vision of “uniting the right.” Unable to continue investing, he sold to Winnipeg-based media mogul Israel Asper, whose CanWest Global was ballooning with acquisitions. Asper later ran into similar issues and sold to Chatham.

Unlike his flamboyant right wing predecessors, Chatham CEO Anthony Melchiorre keeps a low profile—there are no photos of him on the Internet, and he doesn’t give interviews. Postmedia, which now owns over 130 news outlets in Canada, has executives who support the Republican Party (Melchiorre contributed to fellow private equity CEO Mitt Romney’s campaign, and another board member has ties to Trump).

The owners’ politics have tilted the vast conglomerate’s journalism even further to the right, suppressing a union drive at the National Post, and pressuring editors to be more supportive of Conservatives. But their main interest is in extracting maximum cash from each of their outlets.

In a bizarre deal with TorStar in 2017, Postmedia swapped dozens of local papers with the Toronto conglomerate, almost all of which were immediately shut down. When the dust settled, Postmedia had cut 244 jobs and closed 24 newspapers. In 2020, they closed an additional 15 papers, cutting another 80 jobs.

Postmedia’s cuts were a major part of the more than 250 local media outlets in Canada that have closed since 2008.

Chatham has been diligent about creating “efficiencies” and sucking cash out of Postmedia.

In 2020, the New York Times reported that the conglomerate reported losses of $40-million for two consecutive years, and had spent nearly $127-million on debt payments. “During that time,” the Times reported, “it invested relatively little, about $5.4-million, to try to improve the business.” (Figures in USD).

None of the above has stopped Postmedia from scooping up millions in federal subsidies ostensibly aimed at preserving journalism. At the same time that its columnists were bemoaning the giveaways of the CERB, the company pocketed $35-million in relief funds. It seems that, short of funding any journalism, much of those funds went directly onto a balance sheet in the nondescript offices of a hedge fund in New Jersey.

Cable and broadcasting

Private cable and telecom companies have also reached extreme levels of consolidation—a drastic change compared to the 1970s, when there were dozens of regional cable companies.

By 2013, four companies controlled nearly two-thirds of Canada’s television market: Rogers, Shaw, Bell and Quebecor. While cable viewership is on the decline, telecommunications profits are as high as ever.

The slow-motion merger between Rogers and Shaw means power in both media and telecommunications will be even more concentrated. “Efficiencies,” otherwise known as job cuts, are bound to follow.

Cable companies are actually mandated by Canada’s Broadcasting Act to fund community production, including journalism. But the big four have found ways to pocket almost all of that money, with scarcely a word of protest from regulators.

Of course, Canada still has the CBC—an arms-length public broadcaster with a mandate, at least on paper, to represent Canadian society and the political, economic and cultural lives that constitute it. That mandate is a threat to corporate interests, and has been neutralized over time.

The CBC has long faced Conservative threats to defund the institution, and Liberals have taken little action to reverse the right wing tilt of the Harper years. During his time as prime minister, Stephen Harper cut the CBC’s budget continuously and stacked its board with Conservative loyalists. That’s the threat implicit in endless Conservative attacks that claim the public broadcaster is too left-wing.

Cuts to power

Optimistic assessments note that the number of journalists has remained steady despite deep cuts to newsrooms. However, accounting for population growth tells a story of precipitous decline: while there were 415 journalists for every million Canadian residents in 2001, by 2016 there were only 334.

In 2022, journalism jobs are less stable, less unionized, less civically oriented. In recent decades, the proportion of freelancers has more than tripled, while journalist unions have reported drastic drops in their membership. Unifor Local 2000, representing newspaper workers in B.C., saw its membership drop by more than 60 percent since 2010, according to one reporter. Newsrooms that cover public interest beats like city hall or even provincial assemblies have also experienced deep cuts.

Less stable and increasingly precarious journalists are employed by powerful corporate structures that have never been more concentrated, and never been more ruthlessly devoted to extracting value from their employees.

As a result, journalists are required to produce more with less, and have less freedom to follow their own instincts when it comes to fulfilling the public interest part of their role.

Owners and bosses aren’t the only ones getting more powerful.

While journalist positions decline, the public relations industry has seen massive growth. Since the 1980s, the number of workers in public relations and marketing in Canada has tripled. For every journalist in Canada, there are more than 10 people working to influence public perception.

Public interest journalism is cheap, but its absence is expensive

When contemplating solutions, however, there’s no need for excessive hand-wringing. Solving the problem of too few journalists is cheap by government budget standards.

For example, adding 10,000 working journalists with a public service mandate (to the current 13,000, many of whom have no such mandate) would cost about $700 million annually (assuming an average salary of $70,000). That’s about $17 per Canadian each year. Paid out proportional to income, that comes to pocket change for the majority, and the cost of a few meals out per year for the wealthy.

An influx of public interest journalists working in towns and cities across Canada would mean a seismic shift in the scrutiny faced by government officials, business owners, and other centers of power. It would also open countless opportunities for informed local civic engagement and debate, drawing down the numbers tempted to engage in reactionary attitudes and activities.

There are a variety of ideas about how such a hypothetical sum would be allocated. One proposal would see every taxpayer receive a voucher to allocate to the nonprofit media of their choice. Others would allocate resources based on objective criteria, or through federations of nonprofit news outlets, or directly to journalists who meet standards evaluated by their peers. Or a more transparent version of the already-existing Qualified Journalism Organization program, which has requirements for non-profit status and democratic governance.

Whatever the final mix, the mechanism or mechanisms would be the subject of justifiably rigorous debate.

Status quo solutions

Justin Trudeau’s Liberals have undertaken a variety of measures aimed at curbing some of the most extreme civic degradation—and backstop existing media conglomerates and their shareholders.

The Local Journalism Initiative (LJI), for example, provides money to outlets to create positions that perform “civic journalism” in “underserved communities.” (Full disclosure: CUTV, where I am employed, received LJI funding). While recipients include many non-profit and small community outlets, Postmedia has also benefited. In 2020, for example, the media giant announced it was hiring for 12 new positions through LJI funding.

Other measures from the federal government include a tax credit of $14,000 for news organizations for every journalist position. In 2020, Postmedia reported that it was receiving $8-10 million annually in journalism tax credits.

Ottawa has also incentivized subscribers to qualifying news outlets by providing a tax credit for the cost of subscriptions. About 91 outlets currently enjoy this status, and 33 of them are owned by Postmedia. Far from focussing on assisting local and community media, over 80 per cent of qualifying news organizations were part of a parent company that owns two or more publications.

On top of this patchwork of initiatives, the Liberals have introduced two complex pieces of legislation that make major, complex changes to the media landscape: Bill C-11 and Bill C-18.

C-11: Redefining broadcasting and taxing streaming

Bill C-11, sometimes called the Online Streaming Act, promises to tax Netflix, Youtube and other lucrative online streaming and put the proceeds toward funding content made by Canadians.

That “Canadian Content” (CanCon) will be evaluated under the CRTC’s points-based system. The platforms will also be obliged to modify their algorithms to feature CanCon.

Some groups think taxing streamers and channeling some of the revenues to Canadian producers makes sense. They don’t want to lose the opportunity and are campaigning to back the bill.

Others are less convinced, and openly opposed to Bill C-11. CanCon rules lean heavily in favour of large-scale projects by established production companies. Without big changes to CanCon rules, the bill could mean more subsidies for the same conglomerates, shutting out smaller producers.

Community TV and radio stations have taken a more tactical approach. Seeing the legislation as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to change the Broadcasting Act, two community TV federations launched a campaign to close a key loophole and “Rebuild Community Media.” (I was involved in organizing this campaign.)

For years, cable companies had shrugged off their duty to fund community production by defining their own operations as fulfilling that purpose. As a result of a small but enthusiastic mobilization, on June 19 the House of Commons Heritage Committee passed a last-minute amendment that could boost community media’s efforts to close the cable loopholes.

If it passes the Senate, Bill C-11 appears poised to tax streaming giants, but it still allows the corporate-dominated Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to decide who receives that money.

Could Bill C-11 be a net benefit for the public good? Potentially, but not without a fight.

C-18: Making the duopoly pay?

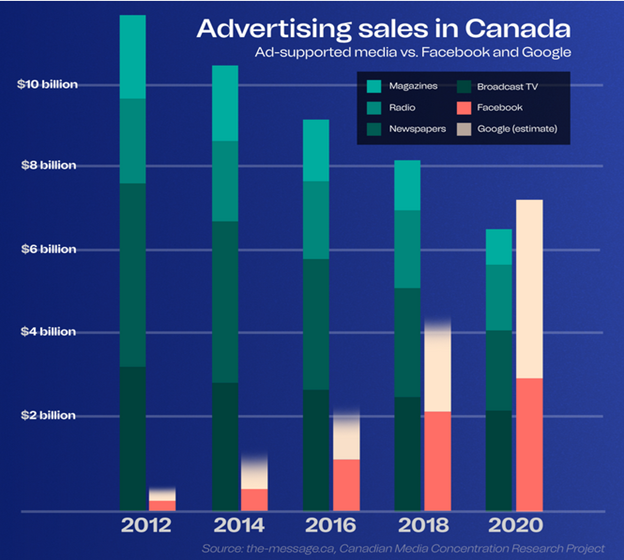

By undercutting advertising markets, Google and Facebook have both played major roles in the large-scale destruction and further consolidation of local news outlets in Canada. When advertising budgets were redirected to the “duopoly,” local newspapers and other providers closed, sold or were shuttered by their corporate owners.

As of 2020, the duopoly’s revenues from advertising in Canada had grown continuously for a decade. By the same measure, ad revenues going to media outlets peaked in 2008, and have been steadily declining, across the board. Radio, television, magazines and newspapers all tell the same story.

In response, the Liberals have turned to what is called the “Australian model,” a scheme that forces big platforms to directly pay media outlets when their users link to journalistic content from their sites.

Under the proposed Bill C-18, Google, Facebook and others would create individual agreements with media outlets to provide them with some share of their advertising revenues.

The legislation has attracted criticism from the same corners as C-11, and support from media conglomerates like Bell Canada. And for essentially the same reasons: corporate conglomerates can count on the CRTC to resolve things left vague in the legislation in their favour.

As with C-11, a coalition has emerged to push for reform C-18 instead of the outright rejection suggested by some players. The Independent Online News Publishers of Canada—a group of more than 100 outlets including many startups and smaller publications—seeks to shore up vague parts of the bill by adding transparency measures, funding in proportion to investment in journalism, inclusion for smaller outlets, and a reduction in exemptions for the duopoly. (The Breach is a signatory to the group’s demands).

Both bills talk tough about taxing the extremely profitable US players that dominate our media landscape. Unfortunately, both also appear to propose the resulting revenues be used to benefit Canadian corporate media giants. That is, unless a force emerges to fight for public interest journalism.

Ownership matters

No one in a news startup feels like they’re repeating history—indeed, that’s usually the opposite of their goal.

But by adopting a for-profit, investor-driven model, the newest generation of media outlets in Canada runs the risk of repeating the same history that led to Postmedia. As the founders of Canada’s new media retire or move on to other projects, their ventures are either shuttered or sold.

When that happens, audiences, reputations and relationships risk becoming assets to be monetized. Thousands of hours of work done by well-meaning (and often underpaid) journalists and editors will, at that point, be bent toward other ends.

While democratic ownership by readers or community members doesn’t guarantee longevity or integrity, it does anchor media institutions with their audience, while creating a pathway for revitalization when leadership hiccups occur.

In democratic, non-profit outlets, the community of readers and viewers, together with reporters and editors, have an opportunity to veto big changes in ownership, and more ability to gather community support and build on the efforts of the past.

A starter kit coalition for media democracy

In the current media ecosystem, nonprofit media—and demands to expand it—is on the margins of the margins.

There has been some initial success amending Bill C-11, the Online Streaming Act, but the path to meaningful results requires reclaiming the corporate-captured CRTC, restoring a public interest tilt to the CBC, and fighting out lobbying battles with cable companies.

The 100+ member coalition of Independent Online News Publishers taking aim at C-18 is the more high-profile association of smaller outlets, but many if not most of its members are for-profit. While in some ways far-reaching, the reforms the coalition is demanding are well short of transformative, and remain compatible with corporate domination of the news.

A transformative shift in how our society thinks about and funds journalism is a necessary step in building a more just future. This transformation requires action from a broad base of media activists and journalists, support from multiple unions and civil society organizations, and the involvement of political parties at multiple levels of government.

The ideological underpinnings of such a coalition scarcely exist. There are still major questions that remain to be answered:

- How much funding do we need for truly public interest journalism, and who should pay?

- What is the best role for the CBC, and what is our strategy for getting there?

- How can we ensure a media ecosystem is publicly funded but meaningfully independent of government or corporate influence?

Even if we had common answers to those questions, mobilizing sufficient support could take years, or decades.

However, a starter kit version of that same coalition—hundreds of supporters, a few MPs, a few dozen media organizations, a few key labour movement allies and a campaigning organization—is in view.

In a volatile and dangerous moment for the media in Canada, relatively small efforts to build alliances around a common vision of journalism in the public interest could have outsized positive results.

Seizing the opportunities before us wouldn’t just benefit journalists and media outlets, but the society they serve.